Technological University Dublin

ARROW@TU Dublin

Dissertations Social Sciences

2015-9

Re-engaging with Education as an Older Mature Student: Their Challenges, Their Achievements, Their Stories.

Helen Graham

Technological University Dublin

Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/aaschssldis

Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons

Recommended Citation

Graham, Helen (2015) Re-engaging with Education as an Older Mature Student: Their Challenges, Their Achievements, Their Stories. Masters Dissertation, Technological University Dublin.

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Social Sciences at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has

been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more

information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected],

[email protected].

Technological University Dublin

ARROW@TU Dublin

Dissertations Social Sciences

2015-9

Re-engaging with Education as an Older Mature Student: Their

Challenges, Their Achievements, Their Stories.

Helen Graham

Technological University Dublin

Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/aaschssldis

Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons

Recommended Citation

Graham, Helen (2015) Re-engaging with Education as an Older Mature Student: Their Challenges, Their Achievements, Their Stories. Masters Dissertation, Technological University Dublin.

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open

access by the Social Sciences at ARROW@TU Dublin. It

has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an

authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more

information, please contact [email protected],

[email protected].

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License

Re-engaging with education as an older mature student: Their

challenges, their achievements, their stories.

Helen Graham

This dissertation is submitted to the Department of Social Sciences, Dublin Institute of Technology, in partial fulfilment of the requirements leading to the award of Masters in Child, Family and Community Studies

Supervisor: Matt Bowden

Department of Social Sciences,

Dublin Institute of Technology September, 2015

Declaration of Ownership

I declare that the attached work is entirely my own and that all sources have been acknowledged.

Signed: ____________________

Date: _____________________

Word count: 14,994

Learning is a treasure that will follow its owner everywhere.

~ Chinese Proverb

Abstract

The decision to re-engage with education at any age can be a significant step for anyone to take. The number of mature learners engaging in further education in Ireland is increasing yearly and public policy continues to encourage lifelong learning. There is a responsibility on institutions providing further education to engage with their students in a meaningful and constructive way. This study addressed an important but neglected area in Irish education research. The study is intended to improve understanding of the mature students’ experience and therefore gives a voice to their stories, their achievements and their struggles. It highlights the needs of this particular cohort of learners who represent a minority within a majority demographic population. Also highlighted is the importance of supporting and assisting mature students to participate fully in education and to achieve their goals within the context of lifelong learning. The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of a group of mature people who had re-engaged with education after several years and were pursuing a further education course. The study was phenomenological in nature and the voice of the participants was central. A mixed method approach was utilised whereby a questionnaire and individual interviews were carried out with the identified research group. The findings of the study indicated significant personal growth and challenges within this cohort of learners. Challenges included: Finances, lack of IT skills, level of academic requirement and time management. Also highlighted in the findings were the different needs of the mature students compared to the more traditional younger student, the importance of awareness among tutors of their needs plus the importance of support services.

Recommendations made in this study include: That prospective students be made aware of the level of academic requirement and the level of IT knowledge required for a course pre-enrolment; that policies and practices be put in place in order to support the older cohort of students; that students be made aware of available supports; promotion of awareness among tutors of the unique needs of the older cohort of learners.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following people who assisted in the completion of this study.

To those who participated in this study, for taking the time to share their experiences with me and for telling their stories in such an open and honest way. Without their input this research would not have been possible. It was a pleasure and an honour to have met them and I wish them well on their education journey.

To Olivia who helped me to get this far, I could not have done it without your help.

To my special friend, Nuala, a solid sounding board and constant encouragement to me on this journey.

To my friends who read and re-read numerous drafts, corrected spelling and grammar and provided much needed constructive criticism.

Thank you to my supervisor Matt Bowden for his help and feedback.

A special thanks to my most beloved children, Aoife, Eoghan and Brian, who stood by me and supported me in every way.

Finally, a dedication to my most beloved and sorely missed father, Kevin, R.I.P. You would have been so proud Dad. You are in my thoughts always.

Table of Contents

Title page

Declaration of ownership ……………………………………………………………………………………..

Quote …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Acknowledgements …………………………………………………………………………………………….

Table of contents …………………………………………………………………………………………………

List of figures …………………………………………………………………………………………………….

List of acronyms …………………………………………………………………………………………………

List of appendices ……………………………………………………………………………………………..

Chapter One: Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………..

1.1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………………………

1.2 Context of study …………………………………………………………………………………………..

1.3 Rationale …………………………………………………………………………………………………….

1.4 Aim and objectives of the research …………………………………………………………………

1.5 Methodology ……………………………………………………………………………………………….

1.6 Definition of key terms …………………………………………………………………………………

1.7 Outline of study……………………………………………………………………………………………

Chapter Two: Literature Review ……………………………………………………………………….

2.1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………………………

2.2 What is further education? …………………………………………………………………………….

2.3 Historical background to adult/further education in Ireland ……………………………….

2.4 Why adults return to education ………………………………………………………………………

2.5 Challenges …………………………………………………………………………………………………

2.6 How adults learn ………………………………………………………………………………………..

2.7 Teaching style ……………………………………………………………………………………………

2.8 Accreditation ……………………………………………………………………………………………..

2.9 Recent developments ………………………………………………………………………………….

2.10 Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Chapter Three: Methodology …………………………………………………………………………..

3.1 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………….

3.2 Research design …………………………………………………………………………………………

3.3 Sampling procedure ……………………………………………………………………………………

3.4 The sample ………………………………………………………………………………………………..

3.5 Data collection methods ………………………………………………………………………………

3.5.1 Questionnaire …………………………………………………………………………………

3.5.2 Interviews ……………………………………………………………………………………..

3.6 Data analysis ……………………………………………………………………………………………..

3.6.1 Quantitative data ……………………………………………………………………………

3.6.2 Qualitative data ……………………………………………………………………………..

3.7 Ethical considerations …………………………………………………………………………………

3.8 Limitations ………………………………………………………………………………………………..

3.9 Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Chapter Four: Findings ……………………………………………………………………………………

4.1 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………….

4.2 Challenges …………………………………………………………………………………………………

4.2.1 Academic component……………………………………………………………………..

4.2.1.1 Referencing ……………………………………………………………………..

4.2.2 Finances ……………………………………………………………………………………….

4.2.3 Computer competence ……………………………………………………………………

4.2.4 Time management ………………………………………………………………………….

4.3 Personal experience ……………………………………………………………………………………

4.3.1 The needs of mature students compared to younger students……………….

4.3.2 Level of education and experience of formal school …………………………..

4.3.3 Reasons for returning to education …………………………………………………..

4.4 Quality of education provision……………………………………………………………………..

4.4.1 Student supports …………………………………………………………………………….

4.4.2 Teaching and learning …………………………………………………………………….

4.5 Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Chapter Five: Discussion ………………………………………………………………………………….

5.1 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………….

5.2 Challenges …………………………………………………………………………………………………

5.3 Personal experiences …………………………………………………………………………………..

5.4 Quality of education provision……………………………………………………………………..

5.5 Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Chapter Six: Conclusions and Recommendations ……………………………………………..

6.1 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………….

6.2 Lifelong learning ………………………………………………………………………………………..

6.2.1 Recommendations ………………………………………………………………………….

6.3 Computer competence ………………………………………………………………………………..

6.3.1 Recommendations ………………………………………………………………………….

6.4 Level of academic requirement …………………………………………………………………….

6.4.1 Recommendations ………………………………………………………………………….

6.5 Time management, finances and external commitments ………………………………….

6.5.1 Recommendations ………………………………………………………………………….

6.6 Teaching and learning …………………………………………………………………………………

6.6.1 Recommendations ………………………………………………………………………….

References ………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Appendices ……………………………………………………………………………………………………….

List of Figures

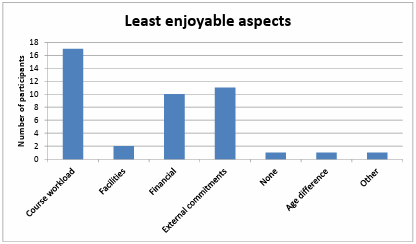

Figure 1 Least enjoyable aspects of being a student

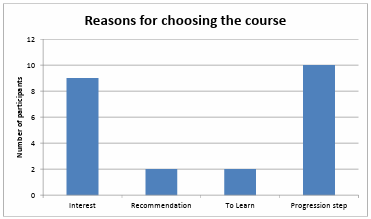

Figure 2 Reasons for choosing the course

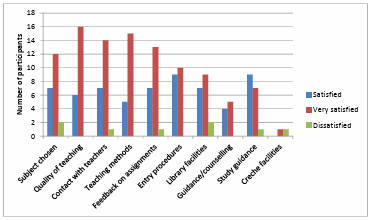

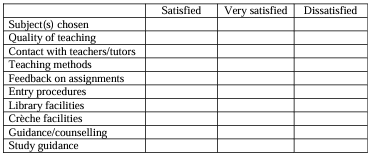

Figure 3 Level of satisfaction with the college

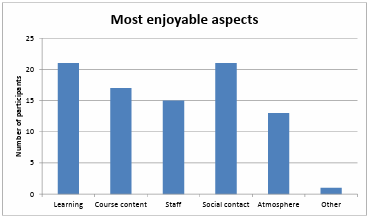

Figure 4 Most enjoyable aspects of being a student

Acronyms

AE Adult Education

AEGI Adult Education Guidance Initiative

AONTAS Aos Oideachais Náisiúnta Trí Aontú Saorálach (National Adult Learning Organisation)

BTEI Back to Education Initiative

CPD Continued Professional Development

CSO Central Statistics Office

DES Department of Education and Skills (formerly Department of Education and Science)

DETE Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment

DIT Dublin Institute of Technology

ETB Education and Training Boards

ETBI Education and Training Boards Ireland

EC European Commission

EU European Union

FÁS Foras Áiseanna Saothair

FE Further Education

FET Further Education and Training

FETAC Further Education and Training Awards Council

HE Higher Education

HETAC Higher Education and Training Awards Council

IT Information Technology

MA Master of Arts

NALA National Adult Literacy Agency

NDP National Development Plan

NFQ National Framework of Qualifications

NQAI National Qualifications Authority of Ireland

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

PLC Post Leaving Certificate

PPF Programme for Prosperity and Fairness

SOLAS An tSeirbhís Oideachais Leanúnaigh agus Scileanna (The Continuing Education and Skills Service)

TC Teaching Council

TCD Trinity College Dublin

UK United Kingdom

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

US United States

VEA Vocational Education Act

VEC Vocational Education Committee

List of Appendices

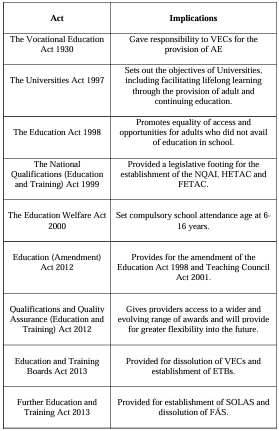

Appendix A Overview of legislation and policy governing further and adult education in Ireland

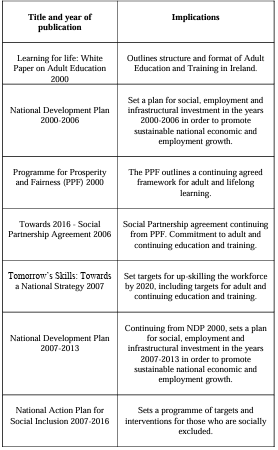

Appendix B Breakdown of numbers of adults in education

Appendix C Letter to gatekeeper

Appendix D Participant information sheet

Appendix E Questionnaire

Appendix F Interview schedule

Appendix G Consent form

Appendix H Sample interview

Appendix I Participant profile from questionnaire

Appendix J Profile of interviewees

Appendix K Sample coding (by topic)

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

1.1 Introduction

This dissertation sets out to explore the experiences of a group of mature people who have re-engaged with education after several years and are on a further education (FE) course in a College of FE. The participants’ voices are central to the study. Thisstudy could be helpful to educational institutions in understanding the particular needs and issues facing such students. This in turn will ensure that they are appropriately supported and catered for in order to make their experience a successful one. Chapter one begins with the context of the research followed by the rationale. It then outlines the aim and objectives of the research plus methodology used. It provides a definition of key terms and concludes with an outline of the study.

1.2 Context of the study

FE originates from Post Leaving Certificate (PLC) courses in the 1980s, and Vocational Educational Committees (VECs) have been the main providers of FE in Ireland. Colleges supporting these students began calling themselves Colleges of Further Education. The first formal recognition of FE was in the Department of Education and Science (DES) publication, Charting our Education Future: White Paper on Education (1995). The FE sector embodies the policy objectives in the 1995 White Paper.

The FE sector has grown over the years and provides education opportunities to over 300,000 students, the majority of whom are mature students (McGuinness, Bergin, Kelly, McCoy, Smyth, Whelan & Banks, 2014). This means that FE is a major provider of adult education (AE). A definition of AE offered for the purposes of the Murphy Report (1973, p. 1) states that AE is: “The provision and utilisation of facilities whereby those who are no longer participants in the full-time school system may learn whatever they need to learn at any period of their lives”. Creating opportunities for adult learners to continue their learning journey improves their quality of life and contributes to the well-being of society.

1.3 Rationale

To connect experience with this study, the author returned to education after an absence of 29 years since doing Leaving Certificate, for a variety of reasons including previous negative experience of education and employment. The author began to wonder if and to what extent her story was reflective of the experiences of mature people returning to education in general. A review of the literature also revealed that these issues require further exploration.

There have been few studies done reflecting the voice of mature students in FE. Therefore this study will add to the small but growing body of knowledge in this field. It will enhance understanding of what it is like to be a mature student, often in classes of much younger students, from their unique standpoint and contribute to improving the service. It has the potential to encourage more mature students to take the often frightening step of returning to education by encapsulating the actual lived experiences of those who have done so.

1.4 Aim and objectives of the study

The overall aim of this study is to explore the experiences of mature people who have re-engaged with education. The objectives are:

To explore the participants’ experience of formal school, their level of attainment and if these influenced the decision to re-engage with education.

To discover why they decided to re-engage with education at this time and the positive and challenging aspects.

To investigate if the needs of mature students differ from those of the younger student cohort.

To explore the area of supports for mature students.

1.5 Methodology

This research is a small-scale, in-depth study. A combination of quantitative and qualitative methods is used. Quantitative methodologies can be useful for providing an overview of the context and, used in conjunction with a qualitative approach, can contribute to a more complete understanding of the individual experience. Data is gathered from a questionnaire followed by semi-structured interviews with mature students on a FE course.

1.6 Definition of key terms

FE refers to education and training after second level schooling but is not part of third level education. The term mature student is often used to differentiate students older than the traditional 18 year old students who have just finished secondary school. FE colleges attract anyone over the age of 16 years and the term mature student in the context of FE are those who are 21 years of age or older. This study concentrates on the experience of students who re-engaged with education in the FE sector after an absence of several years. The participants range in age from 28 to 62 years old.

1.7 Outline of the study

Chapter One

introduces the dissertation and provides an overview of the research including context and rationale. This is followed by the aim and objectives, the adopted methodology, a definition of key terms and an outline of the study.

Chapter Two

is a review of the literature pertaining to AE. It provides a brief description of FE followed by a history of FE in Ireland. This is followed by reasons why adults return to education and the challenges they face. How adults learn, teaching style and the accreditation system, policy and legislation are also identified and discussed.

Chapter Four

presents the research findings which are set out under three main themes that emerged from the data collected. These themes are further categorised into sub-themes. Direct quotes from the participants are used to support the findings.

Chapter Five

is a discussion of the research findings in relation to the literature review and aim of the study.

Chapter Six

contains the researcher’s conclusions from the study and makes recommendations based on the research findings and discussion.

CHAPTER TWO

Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

This chapter is a review of selected literature pertaining to the area of AE and mature adults re-engaging with education. It will explain what FE is, provide a historical flavour of FE in Ireland, and outline key topics that arose. It will show that there is a keen interest in the adult population to return to education. It will highlight some of the many reasons adults choose to do so and the challenges they face. It will also show the importance of hearing directly from those adults as to their experiences.

2.2 What is FE?

The FE sector grew largely out of the PLC programme which has been in existence since 1985. The PLC programme developed as a route into FE for students with Leaving Certificate, and for mature entrants who do not have their Leaving Certificate but possessed experience relevant to the course. Administration, management and staffing are those of a second level school. Colleges providing these courses began to call themselves Colleges of Further Education reflecting the changing profile of the students and indicating the role of the PLC sector in providing second chance education and lifelong learning. FE covers education and training which occurs after second level schooling but is not part of the third level system (DES, 2000). As it falls between two levels it therefore has a less well defined identity than other sectors of education. The profile of FE students varies in terms of age, previous educational experience, gender, ethnicity and life experience (O’Reilly, 2012). It encompasses a spectrum of motivation from economic necessity to leisurely pursuits. The provision of FE includes vocational courses, university access courses, second chance education, community education, adult literacy, programmes for the Travelling community and self-funded adult education. The global economic downturn of the late 2000s coupled with European Union (EU) policy on lifelong learning has seen huge numbers of non-traditional/adult students returning to education.

2.3 Historical background to AE/FE in Ireland

The terms AE, FE, mature/adult students/learners are terms used interchangeably in the literature which perhaps reflects the unstructured system of education provision for those who left the formal education system. Geaney (1998) states that FE in Ireland did not emerge in a planned and ordered way. Present day AE services began with the 1930 Vocational Education Act (VEA) when 33 VECs were established nationally providing full-time continuation and technical education. By 1959 there were over 86,000 adults attending courses (Coolahan, 1981). The VEA allowed for the provision of any course for which there was sufficient demand. This opened the door to further/continuing education.

From 1930 to the 1960s VEC services expanded significantly and in 1969 AONTAS, the National Adult Learning Organisation, was founded. In the same year the government set up an advisory committee on AE which submitted a report, Adult Education in Ireland (Murphy, 1973), to the Minister for Education. A primary concern was with education relating to those who had left full-time education. Two recommendations from this report were implemented: In 1979 50 AE organisers were appointed to develop AE services at local level; and in 1980 The Adult Education Section was established in the Department of Education. The Kenny Report followed in 1984 and as a result VECs established AE Boards. These developments helped to broaden the scope of VECs considerably.

By the 1990s a variety of groups were providing AE programmes. An Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) International Adult Literacy Survey in 1995 showed that almost 25% of the Irish population aged between 16 and 64 scored the lowest level of literacy (OECD, 1997). This triggered a government commitment to developing AE policy. The DES produced a Green Paper: Adult Education in an Era of Lifelong Learning (1998) which set out key areas for improvement within the sector. These included the professional status of teachers and guidance and support for participants. Building on the Green Paper and driven by the EU agenda on lifelong learning, the Government produced the White Paper (2000). This marked the State’s adoption of lifelong learning as the “governing principle of educational policy” (DES, 2000, p. 12). The context of lifelong learning in the EU and in Ireland differs slightly. The Irish focus tends to be on AE whereas the EU encompasses all learning from cradle to grave.

As education and training is now the centre of the modern economy and the world continues to move from an industrialised to a ‘knowledge economy’ (Giddens & Sutton, 2013), education and training policies are becoming increasingly important. FE provision in Ireland is underpinned by the European and national policy context for AE which in turn is aligned to employment and lifelong learning discourse. The literature shows that two discourses are operating in FE. One is the neoliberal discourse where focus is on the needs of the economy and the second focuses on the supportive learning environment which has typified the sector historically.

The White Paper (2000) and the Report of the Taskforce on Lifelong Learning (DETE & DES, 2002) are key pieces of literature in the development of FE and AE provision as they set out the national policy framework for AE. Several more pieces of legislation have been enacted which are relevant to FE services in Ireland (Appendix A).

2.4 Why adults return to education

Returning to education can increase employment prospects, provide educational opportunities missed in the past, facilitate new friendships, and develop new interests. One common outcome is significant personal development and growth (Mercer, 2007; Rogers, 1983). FE can often mark a new start for people taking on the challenge of AE and lifelong learning (Walters, 2000). The vision of the Strategic Framework for FE (Scottish Office, 1999) places emphasis on the FE sector enabling people from every part of the community to pursue lifelong learning for both vocational and personal development. Illeris (2003, p. 13) argues that people are compelled to get involved in education for economic reasons rather than an “inner drive or interest”. Although large numbers of people probably return to education to improve their employment prospects, for others it can be a life changing event resulting in personal growth, intellectual development, and an increase in self-esteem and confidence. According to AONTAS there are approximately 300,000 adults involved in FE programmes each year (AONTAS website). The figure is difficult to quantify due to the range of initiatives available and because no comprehensive national database of statistics for participation in AE is available. A breakdown of the most up-to date figure can be seen in Appendix B. A study by Watson, McCoy and Gorby (2006)

found that considerable numbers of ‘older’ people were taking PLC courses. It also found that the growth in numbers in the PLC sector could be attributed solely to the increase in mature students accessing the sector. They point out that the PLC sector was bringing people back into the educational system. In the case of mature students there was an overwhelming number of females to males taking part across all age categories. The fact that over half of the students participating in PLC courses were over the age of 21 proves the value of these courses in bringing people back to education.

There has been much research into the motivation of adults to return to education but as Rockhill (as cited in Scanlon, 2008) argues studies have concerned themselves more with precision to the expense of the reality as experienced by the people involved. Adults return to education for a variety of reasons including second chance (Coolahan, 1981; Fenge, 2011; Gallacher, Crossan, Field, & Merrill, 2002; McFadden, 1995), up-skilling, employment, promotion, previous experience of education (Salisbury & Jephcote, 2008; Shafi & Rose, 2014), fulfilling a lifelong goal, personal growth, self-actualisation (Waller, 2006), passing the time, learning a new skill, improving on an old skill, significant life event (Bridges, 2004; Sugarman, 2001; Walters, 2000), changing demographics (UNESCO, 2014).

A report on adult learning and education (DES, 2008) states that the philosophy of AE/FE in Ireland is to provide a range of education programmes for young people and adults who have left school early or who need further education and training (FET) to enhance their employment prospects. The main objectives of the further and adult education programmes funded by the DES are to meet the needs of young early school-leavers; to provide second chance education for people who did not complete upper secondary education; to provide vocational preparation and training for labour market entrants and re-entrants (DES, 2008).

Waller (2006) argues that when and why adults return to education is highly individualised. A study by Aslanian and Brickell (as cited in Walters, 2000) in the United States (US) in 1980 found that 83% of learners 25 years and older surveyed were engaged in learning due to life events. A study of older adults’ motivation for engagement with FE and higher education (HE) in Scotland by Findsen and McCullough (2006) demonstrated that the majority of participants undertook learning for more than one reason. The main motivators highlighted in this study were personal growth, subject interest, life transitions, work/career change and the desire to learn something new. Work-related considerations were the most significant motivating factor. A study by Gallacher, Crossan, Leahy, Merrill and Field (2000) found a complex interaction of a number of factors as to when and why adults engage

with education.

Some key motivating factors found were self-development, employment, involvement in community and voluntary organisations, overcoming health and related problems. A longitudinal study by Orth, Trzesniewski and Robins (2010) found that engagement with education had a significant positive impact on self-esteem.

Gallacher et al. (2002) in their discussion on adult returners to FE make the point that by the 1970s the FE sector in the United Kingdom (UK) was an important avenue back to education for those who wanted a second chance at gaining qualifications. Fenge (2011) undertook a study into the experiences of mature students on a foundation degree course in a college of FE in the UK. She found that participants had difficult early educational experiences and unrealised potential (Britton & Baxter, 1999) and their choice of further study was a way of getting a second chance.

A study by Walters (2000) looked at the experiences of mature students in HE regarding motivations, expectations and outcomes, where the main emphasis of the research was on the students’ own perceptions. This study found that education can be a great agent of change in people’s lives. Although this was a study in the HE sector the issues raised are similar to those in FE despite a significant difference in student profile.

Gould (1978) in speaking about growth as the obligation and opportunity of adulthood, states that rather than being a ‘plateau’, adulthood is a time of change. Furthermore, key events in our lives can make us see ourselves as creators of our lives rather than living what we think is our destiny (Gould, 1978). This fits with Mezirow’s transformative learning process, which he describes as emancipatory (Mezirow, 1981), whereby adults recognise their culturally induced dependency roles and relationships and take steps to change it.

Malcolm Knowles, an influential figure in AE who developed the theory of andragogy (the education of adults), refers to three ultimate needs and goals of human fulfilment (Knowles, 1980). Prevention of obsolescence is one. This arises from the fact that traditionally education was considered the preserve of youth whereby everything one needed to know was learned at that stage. In this rapidly changing society and era of lifelong learning this is no longer valid. The second need referred to by Knowles is the need for individuals to achieve self-identity through development of their full potential. From a psychological point of view the literature will tell us that we all possess a need for complete self-development (Knowles, 1980). Maslow (1968) in his desire to understand human motivation arranged human needs in a hierarchal order. As each need is met one may reach the highest level called self actualisation. Maslow believed that everyone is capable and desires to move towards self-actualisation but that progress can be interrupted by unmet needs at the lower level. Life events such as losing a job, death of a family member can cause such interruptions. Bridges (2004) and Sugarman (2001) maintain that these kinds of significant life events prompt some to take stock of their lives and take up new interests, including education. Knowles (1980) writes that people whose basic needs have been met are motivated to actualise their full potential. In this regard it is then the role of the educator to assist the learner to “whatever level they are struggling” (Knowles 1980, p. 29). The third need according to Knowles is for the individual to mature; moving from dependent (child) to self-directed (adult) being. If one goal of the adult educator is to assist individuals to continue a maturing process throughout life, this then “provides useful guidelines for the development of a sequential, continuous and integrated programme of lifelong learning” (Knowles, 1980, p. 32).

2.5 Challenges

Most adults benefit from returning to education (Dawson, 2003), however adults face considerable challenges when taking that step. Some of the biggest challenges include lack of time, finances, confidence issues, lack of support systems, accessibility to college campus and classes, feelings of being too old to learn and social anxieties (Dawson, 2003). Murphy and Fleming (2000) in their research into mature students in HE found a number of challenges facing the students. The most significant were financial, relationships with partners, other external commitments, the academic components of essay writing and exams. These issues are similar to those facing students in FE and can cause considerable anxiety for students which can negatively impact on their education. Online courses can help those who do not have the time to attend a college and also those who may feel intimidated by being in a class of much younger students. Colleges around the world are now offering courses outside of the typical term time to facilitate a diverse student population who have jobs and families.

Although numbers are growing yearly in Ireland and worldwide the mature student cohort is likely to be in the minority in the FE classroom. Watson et al. (2006) found that over half of the students participating in PLC courses in Ireland were over the age of 21. This growth in older learner numbers along with online options is helping to remove some obstacles for the older student which may prevent their returning to education. One initiative resulting from the DES White Paper (2000), called the Back to Education Initiative (BTEI), provides flexible options such as part-time, modular or flexible learning options.

Mature students re-engaging with education after a considerable length of time since formal school can be at a disadvantage compared to the younger students who recently sat their Leaving Certificate exam. Specifically the challenges of essay writing, study skills and lack of exam practice can present significant challenges for mature students, particularly if they have not written an essay or sat an exam since school (Murphy & Fleming, 2000).

Education systems all over the world are changing rapidly, partly due to developments in information technology (IT) (Giddens & Sutton, 2013). Lack of IT skills is a typical problem among older learners. Studies done in the UK, Australia, by the National Adult Literacy Agency (NALA) in Ireland and by the European Commission (EC) showed that large numbers of older learners had little or no IT skills (EC, 2013; NALA, 2009; Taylor & Rose, 2005), and that IT skills are a powerful tool to raise the levels of literacy and numeracy among adult learners (Kambouri, Mellar & Logan, 2006; NALA, 2009). NALA (2009), The Further Education and Training Strategy 2014-2019 (DES & SOLAS, 2014) and Kambouri et al. (2006) suggest embedding IT skills within the adult literacy programme. Taylor and Rose (2005) stress that low IT skills are a barrier to learning but also have an impact on the successful engagement and retention of older learners.

2.6 How adults learn

Illeris (2003) speaks about the rapid increase in AE programmes due to the fact that lifelong learning has become more integrated into employment policy rather than an issue of emancipation. He further states that adults are less inclined to learn something they do not perceive as meaningful to them. Whereas Malcolm Knowles maintains that andragogy is a specific theoretical and practical approach based on a humanistic conception of self-directed and autonomous learners and teachers as facilitators of learning (Knowles, 1980). Knowles in describing the characteristics of the adult learner states that as we develop towards adulthood:

the need for self-direction increases;

adults need to know why they need to learn something before commencing their learning;

adults have a psychological need to be treated by others as capable of self direction;

adults have accumulated experiences which can be a rich resource for learning;

adults have a problem-centred orientation to learning;

readiness to learn becomes orientated towards the adult’s need to perform social roles;

adults apply new learning immediately;

the more potent motivators for adults are internal. (Knowles, 1980)

Some adults may return to education because life circumstances, experiences, or life stage has caused them to think that perhaps their view of the world has been limited and they want to expand their thinking. Jack Mezirow believed that as we mature and gain more experience our perspectives can be challenged as they cease to fit in with our actual experience of the world (Mezirow, 1981). Whereas in childhood learning is formative (derived from formal sources of authority and socialisation), in adulthood it is transformative as adults are more capable of seeing distortions in their own beliefs, feelings and attitudes. Mezirow (1981), as a result of his study into women participating in college re-entry programmes, developed the term ‘perspective transformation’.

In order to continue towards independence we need to develop perspectives that are more inclusive and integrative of our experiences. This transformative learning process can transform our mindsets, or frames of reference, to be more inclusive and open to change based on the ability to question or critically reflect on ourselves and on society. This in turn will lead to empowerment and change in the learner.

Paulo Freire (1970) argued that educative processes are never neutral; they will be either liberating or domesticating for the learner. Freire (1970) refers to the ‘banking’ concept of education. By this Freire was comparing students to empty accounts to be filled by a teacher, making the students into receiving objects who adjust to the world and thereby inhibiting creativity. The problem with this is that there is a danger the students may become dependent on the teacher for knowledge and do not learn to think for themselves. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2014) states that a paradigm shift is required in order to move from knowledge-conveying instruction towards learning for personal development and the release of creative potential. Dewey (1938) rejected the notion of the educator taking on the role of ‘dictator’ and advocated for students being provided with opportunities to think for themselves and be allowed to articulate those thoughts in a more co-operative educational community. This approach is ultimately more suited to adult learners whereby they bring a wealth of experience and knowledge into the classroom, which they got by living (Murphy & Fleming, 2000). The diverse range of academic ability coupled with external commitments many mature students have has implications for teaching and learning in FE.

2.7 Teaching Style

Teachers are the key facilitators of learning and appropriate learning approaches are especially important where there have been negative experiences of prior learning (Scanlon, 2008). The banking model referred to above has no place in the realm of adult learning. The constructivist approach, whereby the learner is actively involved in their own learning building on previous knowledge and experience, is more suited to adults returning to education. Following on from Knowles’ characteristics of the adult learner it follows that adults need to be involved in every aspect of their learning. Therefore educators of adults need to think about their teaching as a collaborative and creative process where learning can be agreed upon mutually, where the learner is in control, and where the educator’s role is to be a facilitator and guide. In a study by Mooney (2011) it was found that participants were surprised to be so involved in their learning as there was an expectation that college would be like school.

The more adult learners are involved in their learning the more their confidence and self-esteem will be impacted and the more likely they are to continue in their education.

Adults come to courses with a variety of experiences and varied educational backgrounds but teachers in FET are more likely to be qualified to teach second level. In the area of AE there has existed a presumption that primary and secondary school trained teachers can apply their expertise to the teaching of adults (Bassett, Brady, Fleming & Inglis, 1989). Yeaxlee, who promoted the student-centred approach to learning, states that adults are a heterogeneous learning group and therefore their needs cannot be met by formal classroom teaching methods (Yeaxlee, 1929, as cited in Jordan, Carlile & Stack, 2008). The McIver Report (2003) found that many students felt the teaching style was more appropriate to adolescents than adults. One of the recommendations of the McIver Report was that the duty of care to FE students should be modified in line with maturity and adult status. Its vision was to provide a sector which recognised real adult learning needs and where staff training would respond to adult learners positively and imaginatively. It called for funding to be invested in the FET sector for resources required by FET providers. These recommendations remain largely unimplemented due to prohibitive costs (ETBI, 2014). However, there are now ten courses for teachers within the FET sector which are accredited by The Teaching Council (TC) (TC, 2011). The Education for Employment Project (2007) makes the point that educators need to be able to adjust not only to diversity of learning styles but also to diversity of age. The DES White Paper (2000) refers to appropriate teaching strategies for adults as a key element of the framework of lifelong learning. McDonnell (2002) states that adult learning issues should be an integral part of teacher training. According to the TC (2011) in order for a FE teacher education programme to achieve accreditation from the TC, qualification at post-primary/level 8 on the National Framework of Qualifications (NFQ), (NQAI, 2003) is required. The University of Washington produced a toolkit for teaching adults based on Knowles’ theory of andragogy. It acknowledges the differences in teaching adults and stresses the importance of having a knowledge of how adults learn (University of Washington, 2012). Teachers in FE colleges need to have the skills and knowledge of adult learning in order to create meaningful and relevant social contexts in which learning can take place and to adopt adult appropriate curricula, programmes and teaching methods (Coleman, 2001). This presents a significant challenge for educators as most FE classrooms can have students of 16 years and up.

2.8 Accreditation

The Irish NFQ was established in 2003 and is the framework through which all learning achievements is measured in a coherent way. The NFQ puts the learner at the centre of the education and training system in Ireland. It includes awards made for all types of learning from initial learning up to Doctorate no matter where the learning is gained.

2.9 Recent developments

In 2013 SOLAS (An tSeirbhís Oideachais Leanúnaigh agus Scileanna) was established under the FET Act 2013. SOLAS’ remit under the DES is to oversee planning, co-ordination and funding of training and FE programmes. In 2013 the VECs were dissolved and 16 Education and Training Boards (ETBs) were established under the Education and Training Boards Act 2013. ETBs manage and operate second level schools, FE colleges and a range of adult and FE centres delivering education and training programmes. The Adult Education Guidance Initiative (AEGI), informed by the DES White Paper (2000), is aimed at helping individuals make informed education, career and life choices and is available from the ETBs. It provides ongoing guidance which supports the student’s motivation to continue with a programme, especially in cases of previous negative educational experience.

The FET Strategy aims to direct and guide transformation of the FET sector over five years. It aims to provide an integrated FET system and improve the standing of FET in Ireland, among other things. The Strategy puts employability and the economy firmly at the forefront of FE while still acknowledging the value it will play in social inclusion. Education is being presented by the Irish Government and the EU as key tomeeting the challenges facing the global economy, however a predominant focus on employment could risk exclusion of those not connected with the labour market. The success of the FET strategy remains to be seen.

2.10 Conclusion

This chapter has examined literature pertaining to the area of AE and mature adults re-engaging with education. It has looked at historical developments in the area of FE and at policy and legislation which has shaped it. The many and varied reasons why adults return to education have been explored and how adults learn has been described. The challenges faced by older people returning to education as well as the positive elements have been discussed. The challenges for educators to cater for this student cohort have also been highlighted.

A review of existing literature has shed light on the following issues that warrant further exploration:

Is prior experience (positive or negative) of formal school and/or the length of time away from education a factor in deciding to re-engage with education?

Mature students returning to FE is a relatively under-researched area compared to the HE sector. Some issues facing mature students are similar in both sectors. However, it is not appropriate to extrapolate findings from studies in the HE sector and compare them to the FE sector because the two sectors attract completely different groups of mature students with regards to background, qualifications, and knowledge of techniques and strategies required for exams and essays.

The needs of mature students differ considerably from the younger cohort with regards to supports, prior experience of education and length of time away from education, as well as varying abilities according to age, for example memorizing for exams.

In order to gain further insight into the reality of re-engaging with education as an older person this study will now investigate the experiences and perspectives of mature students who have done so.

CHAPTER THREE

Research Methodology

3.1 Introduction

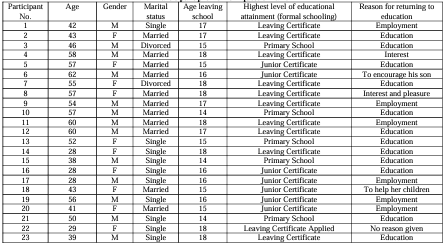

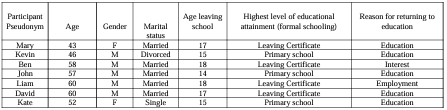

The main aim of this study is to explore the experiences of a group of mature students who re-engaged with education. A review of existing literature has shown that large numbers of adults are returning to education for a variety of reasons. This research involved participation of 23 mature students currently attending a College of FE. Some participants finished formal schooling and some did not but in each case there was a gap of between 10 and 46 years before re-engaging with education.

This chapter describes the chosen research design and methodological approach taken. The decision to use a questionnaire and interviews is explained. Details of the sampling procedure are outlined as are data collection and data analysis techniques used. Ethical considerations and limitations are discussed.

3.2 Research design

According to Bryman (2012) a research design provides a framework for the collection and analysis of data. As this enquiry involves investigating the experiences of mature students it is open-ended and exploratory in nature. The main purpose of qualitative research is to understand the experiences from the participants’ perspectives. Marshall and Rossman (1999, p. 2) state that qualitative research is “pragmatic, interpretive, and grounded in the lived experiences of people”. By using a qualitative research method there is an opportunity to engage at a deeper level with the experiences of the mature students, whereas quantitative methodologies are more constrained in what they contribute to understanding lived experience. However, quantitative methodologies can be useful for providing an overview of the context and, used in conjunction with a qualitative approach, can contribute to a more complete understanding of the individual experience.

This study adopted a phenomenological approach, which is a design of enquiry where the researcher accesses, analyses and reports on the lived experience of individuals about a phenomenon as described by the participants (Creswell, 2014; O’Leary, 2010). Phenomenological research captures the meaning of the experience for individuals who have all experienced the phenomenon (Creswell, 2014), such as the meaning of returning to a setting which they had left many years before, and therefore supports the aim of this research.

While the topic under investigation relates to human experience, which lends itself naturally to qualitative methods, a quantitative method is also used to provide an overview of the participants. As lived experience is best measured through words as opposed to numbers the bulk of the research focussed on the qualitative method of interviews. A questionnaire (n=23) was administered in order to gather quantitative data followed by interviews (n=7) to gather qualitative data. The questionnaire provided participant demographics and brief information on education history and choices. The interviews explored the participants’ lived experience of returning to education in greater depth.

3.3 Sampling procedure

The validity and reliability of a study depends on good sampling decisions (Marshall & Rossman, 1999). Denscombe (2007) states that the researcher needs to ask the question “given what I already know about the research topic …., who or what is likely to provide the best information?” With this in mind, a purposive sampling technique was employed. Participants relevant to the study (Sarantakos, 2013) were chosen by targeting mature students in a college of FE who had re-engaged with education.

When attempting to access a research sample researchers are obliged to acquire permission from ‘gatekeepers’, that is, those who control access to the information which the researcher seeks (May, 2011). Contact was made by written letter to the principals of five colleges of FE seeking a meeting to discuss access to mature students for the purposes of doing a research project (Appendix C). An information sheet was also enclosed which outlined the purpose of the study and what participation would involve (Appendix D). These letters were followed up by telephone calls and emails. The principal of one college agreed to meet and discuss the project. Having met the principal and answered any questions the researcher was given permission to access three classes in the college where there were students that fulfilled the criteria outlined above. The principal, on the researcher’s behalf, sought and was granted permission from the teachers of these three classes to gain access to the mature students during class time. A date and time was agreed for this to take place. As end of term exams were imminent the researcher had a window of one week to speak to the classes and find volunteers.

3.4 The sample

The researcher was given access to a Return to Education class, a Social Care class and a Performance class. Visiting each of the classes in turn the researcher introduced herself and explained the purpose of the visit. The term mature student can cause confusion as it is used interchangeably with adult learner and anyone 18 years old and over is an adult. Clarification was required in order to capture the mature students who had re-engaged with education. The researcher then distributed a short anonymous questionnaire (Appendix E) to students willing to fill one out. The questionnaire facilitated accessing participants who would be willing to take part in an interview by including a question to this effect. Only those willing to be interviewed were asked for contact details to be included in the questionnaire.

3.5 Data collection methods

Data were gathered using questionnaires and interviews which were deemed valid for this study. The rationale for selecting these methods is now outlined.

3.5.1 Questionnaire

A short, preliminary questionnaire was chosen to be administered for several reasons. Firstly, the researcher felt that this method would be an efficient way of accessing the mature student population from the general student population in the college. Secondly, the questionnaire would provide an overview of the demographics and characteristics of the mature student population. Thirdly, and most importantly, it allowed the researcher to identify students willing to participate in interviews. Finally, the questionnaire could identify issues to be explored in greater depth in interviews.

The questionnaire was first piloted and adjustments made in order to clarify the questions that caused confusion. The tutors gave time at the beginning of class for the researcher to explain the project and make a request for volunteers. The researcher was on hand for any clarifications needed and this also facilitated efficiency of collection and the highest rate of return.

3.5.2 Interviews

The most common types of interviews used in qualitative research are semi-structured and unstructured interviews. Both are designed for data collection on the basis of the capacity to provide insights into how research participants view the world (Bryman, 2012) and have the common aim of discovery (Denscombe, 2007). Semi-structured interviews allow for specific topics to be covered while still allowing a great deal of leeway for the interviewee in how to reply without sacrificing the focus of the interview (Barbour, 2008).

Unstructured interviews resemble a conversation (Bryman, 2012) where the interviewee is allowed to respond freely to perhaps just one question. As there were specific issues that the researcher wanted to explore with all interviewees a semi-structured interview was considered to be most suitable. Semi structured interviews allow for flexibility in answering while still covering vital issues which allows for comparability when analysing data, and is therefore valid.

The students willing to be interviewed were contacted by email to confirm their willingness to participate, to thank them and to arrange dates and times. The participant information sheet was attached explaining the research project and what participation would entail. A pilot interview was conducted which led to clarification of some questions that caused a misunderstanding on the part of the pilot-interviewee.

Qualitative interviews require a great deal of planning (Mason, 2002) in order to generate relevant data. To ensure a focus on the research objectives an interview schedule was devised (Appendix F). An attempt was made to focus on topics rather than specific questions in order to generate open-ended questions and to allow for flexibility for participants to develop their ideas and allowed the interviewer to pursue opportunities that may arise during the interview. Given the semi-structured nature of the interviews, the course of the interviews varied slightly from one interviewee to the next.

In the interests of putting interviewees at ease and to make the experience as comfortable as possible, each participant was given the option to choose their preferred location and time for interview. The least intrusive recording device was selected by the researcher in the hope that its presence would not put the interviewees off. Before beginning the interview the interviewees were reminded of the voluntary nature of their participation and that withdrawal was an option at any stage of the process. Each interviewee was then asked to read the participant information sheet again and sign a Consent Form (Appendix G).

Time was given for questions/clarification before beginning the interview to help establish a relationship of trust between interviewer and interviewee. Participants were assured and reminded of the confidentiality of their participation before commencing. The duration of each interview varied between twenty and forty minutes. Interviews were audio-recorded with the consent of the participants and then transcribed verbatim by the researcher to ensure reliability and accuracy of information (Seidman, 2006). Recording ensures accuracy of data for subsequent analysis and allows the researcher freedom to focus on the interview and to make observational notes without getting distracted by having to concentrate on taking down what was said (Biggam, 2009; Bryman, 2012). A transcription of an interview is included in Appendix H.

3.6 Data analysis

The methods used to analyse the data are presented in this section.

3.6.1 Quantitative data

The quantitative data were gathered using a questionnaire which were then analysed to provide an overview of the mature students in this study. A participant profile was built from the data (Appendices I and J) and further data are presented in figures 1-4.

3.6.2 Qualitative data

Data from the transcripts of interviews were collated by the researcher and thematically analysed. The researcher read and re-read the transcripts in order to become familiar with the data and then coded the data by organising excerpts from the transcripts into categories (Appendix K). The researcher then searched for connecting threads and patterns within the categories from which themes were identified. The data was then grouped into three main themes in accordance with the aim and objectives of the study. The three themes are: Challenges; Personal experiences; Quality of education provision. The findings under each of these themes are presented in chapter four and discussed in chapter five in line with the literature review.

3.7 Ethical considerations

Researchers need to be alert to the ethical implications of any decisions they make (Punch, 2014), therefore careful regard to ethical issues is needed when engaging in social research at every stage of the process. The well-being of the participants is paramount. In the collection and analysing of data and the dissemination of findings it is expected that the rights and dignity of participants are respected, that any harm to participants arising out of their involvement in the research be avoided, and that the researcher operates with honesty and integrity at all times (Denscombe, 2007).

The nature of social research is such that it can include anything from consumer preferences to drug testing. However, the underlying ethical principles remain the same and fall under three categories; protecting the interests of participants, avoiding deception or misrepresentation, informed consent (Denscombe, 2007). The researcher communicated with openness and honesty at all times to participants. An information sheet was disseminated to all participants clearly detailing the purpose of the research, how it would be carried out and what participation would entail. The information also covered issues of anonymity, confidentiality and the voluntary nature of the study. Participants were reminded at each step of the process that withdrawal was an option at any stage. Assurances were given that any data either written or recorded would be stored securely and only accessed by the researcher. It was explained that no names or any form of identification would be used anywhere in the final report. The researcher’s contact details were included in the participant information sheet should any participant have any questions. Having discussed the research and clarified any outstanding issues, the participants were then asked to sign a consent form.

This study was approved by the Head of School of Languages, Law and Social Sciences under the research ethical guidelines as set out by the Dublin Institute of Technology.

3.8 Limitations

Due to the small scale sample in this study it cannot be assumed that the findings are representative of the experiences of all mature students who have re-engaged with education. It was not the intention of this researcher to make generalisations but rather to portray the reality of the experiences of a selected group of participants. Despite the small scale sample however, findings do show consistencies that could be further investigated by other researchers.

When using interviewing for data collection there is a danger of developing a close affinity with the interviewees to the extent that it may be difficult to separate the stance of the researcher from those of the interviewees. The researcher is herself a mature student returned to education and therefore aware of possible ‘interviewer bias’ (Bryman, 2012).

Sarantakos (2013) rates interviewer bias in face-to-face surveys as ‘high’ compared to telephone and mail surveys which rank as moderate and nil respectively. Social research is influenced by a variety of factors, one of which is the impact of values on the research. Values can reflect the personal beliefs and feelings of the researcher (Bryman, 2012). In order to avoid bias and for the research to be valid this can be addressed partly by what Bryman (2012) terms ‘reflexivity’. Reflexivity means that researchers “reflect on the implications of their methods, values, biases and decisions for the knowledge of the social world they generate” (Bryman, 2012, p. 393). Edmondson (2007) maintains that in reflexive social science researchers should declare their biases and expose proclivities influencing outcomes. It would be untruthful for this researcher to state that this research has not been influenced by her own experience. However, as this disclosure neither validates nor invalidates the research outcome (Gergen & Gergen, 2007), this author nevertheless undertakes to ensure that any researcher bias has been minimised by being aware of and acknowledging its presence in this study.

One college responded out of five colleges contacted. The researcher had a window of one week to find a sample before the start of final exams and end of term. The number of mature students in the college was small and not every student agreed to take part in the study. Therefore the final sample was limited. Out of three classes that the researcher spoke to 23 students agreed to fill out the questionnaire; seven of these agreed to be interviewed. The seven interviewees all came from the same class. This implies that the findings will be somewhat biased rather than a more balanced cross-section of mature students studying different subjects.

3.9 Conclusion

This chapter has justified the use of a quantitative research method combined with a qualitative method which meets the aim of the research. It describes the selection and sample of participants and explains the choice of data collection methods. Data analysis is described, ethical considerations were established and limitations acknowledged. The next chapter will present the findings from the questionnaires and interviews using direct quotes from the participants.

CHAPTER FOUR

Findings

4.1 Introduction

This chapter outlines the findings from quantitative and qualitative data that were gathered during this research. The data will provide an overall picture of the experience of a small number of mature students who re-engaged with education in a College of FE. In keeping with a phenomenological approach the focus of this chapter is to present the raw data as it was reported. The data are presented under three headings: Challenges; Personal experiences; Quality of education provision. Data from the questionnaires are anonymous therefore participants are identified by a number and pseudonyms are used to protect the identity of the interviewees. An overview of participants who took part in the questionnaire and interviews can be seen in Appendices J and K respectively.

The quantitative data in this research were gathered from a questionnaire. Most of the qualitative data for this study were gathered through semi-structured interviews; however some qualitative data were also gathered from the questionnaire.

4.2 Challenges

There were many challenges reported by this sample group which are included in the following analysis of data.

4.2.1 Academic component

A significant number of participants found the course very demanding. Seventeen survey participants selected course workload as one of the least enjoyable aspects of college (Figure 1).

There was no qualitative data gathered on the questionnaire with regards to the academic component of the course, however this issue was explored at interview.

When asked how they managed the demands of studying and assignments there was unanimous opinion among participants that the academic component proved very difficult.

John who had not been in education for 40 years knew that the academic component of the course would be challenging for him.

“I always felt that the academic side might catch up on me. When I started and I got to the class I realised just how far back in the class I was. The challenges in the second year were much tougher than in the first year.”

Kate found it “a bit of a shock”, whereas David who was expecting it to be “a bit of a doddle” discovered that it was “intense”.

Kate and Kevin both left school at 15 and neither of them had written an essay before.

“The whole format of essays because that was probably the biggest thing for me was having to learn how to write an essay.” (Kate)

“I never done an assignment to be honest. I didn’t really understand when I was given the brief, you know, I’d have to go off and ask someone.” (Kevin)

Ben realised when he was given his first assignment that it had been a long time since he had written an essay.

“I got the first essay in first year, I realised it was the first time in 38 years that I had ever written an essay and it was a 2000 word essay. I’m not sure I’ve ever written a 2000 word essay before then.”

Liam struggled with exams and felt his age was a contributing factor.

“Exams were hard I found ……… trying to remember that guy’s name or trying to remember that theory, anything like that is a lot harder when you are over fifty or sixty.”

4.2.1.1 Referencing

Referencing proved to be an issue with some students, one of whom had never heard of it before.

“….. the biggest thing for me was having to learn how to write an essay and how to reference it; I’d never even heard of that before.” (Kate)

4.2.2 Finances

Almost half of the participants surveyed chose finances as one of the least enjoyable aspects of college (Figure 1). Of those that chose finances eight were unemployed while two were employed.

For Kate, a single mother with dependents, finances were of particular concern.

“It was difficult; I didn’t get any grants you know. I was scrimping by really to be honest with you.”

Kevin who had to work and was studying at the same time, making up lost hours at work was essential to his being able to continue his education.

“I’d have to try and stay out later at the weekend to make me money up you know. That’s the only way I could really do it.”

John who left school at fourteen and felt he had “missed out” academically was keen to continue to the next level but felt that finances would keep him from proceeding with his education.

“Financially I would have to look at the cost of the course first because em that’s just the way things are. Going on to do the degree course I think you’d be in to the thousands …… and that’s totally out of the question.”

Liam was on the dole and found the costs associated with returning to education a cause of concern.

“Financially I suppose the financial thing was getting across town and getting in to college.”

4.2.3 Computer competence

Computer competence, or IT, is considered to be an essential requirement for social and economic participation as well as for access to a wide range of services and information in the modern world. For some participants who lacked computer competence acquiring these skills was of significant practical importance. Two participants found the lack of computer knowledge a hindrance to their education and felt that it would be important to take a computer course before entering college in order to be able to keep up. Having to learn computer skills alongside the course was an added burden.

“The whole computer thing was a bit daunting for me. That’s not included in your course and you’d really have to know all that stuff before you come in.” (Kate)

Ben commented on what he felt was a general misconception about young people and technology.

“I’m quite technologically savvy but a lot of people my age aren’t. Mind you a surprise to me was that some of the young people aren’t either. Everyone says young people are whizzes and in my experience that’s not necessarily the case.”

4.2.4 Time management

Several participants spoke about the challenge of managing their time. Some were juggling family commitments and others jobs while trying to fit in assignments and studying for exams. In some cases managing their time improved as they progressed through the course. Most participants had adult children, but Kate and Ben had children of school-going age. Kate had to work around when her children were at school and found studying in the college was better than studying at home due to the distractions of household chores.

“I was actually going home and thinking ah grand and getting into my normal routine and forgetting about the homework. You get distracted very easily especially when you are a mother.” (Kate)

“Em yes assignments the whole time management thing, I kinda got better at that as I went along.” (Ben)

Mary who has children and was trying to run her own business found managing her time particularly difficult. She eventually had to close the business in order to continue her studies.

“It has been stressful trying to juggle everything. Yeah, time management, with the business, with the kids. When you have kids your time is just not your own.”

Liam felt that the group work was a drain on his time.

“This is where the time management comes in, trying to satisfy somebody who is working who is in doing the same course as me. I felt a lot of my time was wasted.”

Liam also felt that his age affected his ability to study and had to make an extra effort to organise his time.

“By being older I found you know harder to study in the evenings but when I allocated the time and I made space for myself I did better.”

Kevin was juggling his full-time job with his studies while at the same time dealing with health issues. He found it very stressful to fit everything in.

“I was going into college and going home to do my work in me job and going home to do my assignments. I was sitting there all night. I was going to be up all night anyway, so that’s the way I had to be.”

David who had retired and was returning to pursue something he loved was surprised at the intensity of the course. He was not prepared for the amount of time required to get the work done.

“I had this view when I was coming back that oh you know you do about twenty hours in the week in college and sure that’s only a part time job …… the rest of the time is all your own. I wouldn’t be surprised if I’d been putting fifty or sixty hours a week in the whole thing you know.”

4.3 Personal experience

Despite the challenges mentioned above there was evidence of significant personal growth among participants. In light of their experience participants were asked if they would recommend other mature people to return to education. There was an overwhelmingly positive response to this.

Kate found the social aspect particularly rewarding.

“It’s been a very positive experience for me and it has impacted my life. I have a whole new spectrum of friends.”

Kevin found that it gave him a new lease of life plus a huge sense of achievement and a much needed boost to his confidence.

“This course has given me so much; it’s given me like another language. I didn’t think I’d finish it but I did, so you know, I was chuffed with myself. I didn’t finish school so that was my big thing you know.”

John feels that an unfinished part of his life came together by re-engaging with education after so long.

“It’s been brilliant. Like me, they’ll [other mature people] probably leave a bit better than when you came in. I sort of feel now that a little bit of a jigsaw puzzle that was missing is now in place.”

4.3.1 The needs of mature students compared to younger students

Interviewees were asked if they felt the needs of mature students differed from those of younger students. The general consensus was that needs differed significantly between the two cohorts. As discussed above (section 4.2.3) IT was an issue that posed considerable difficulty for the older cohort and they were, in the main, of the opinion that IT was not an issue for younger students.

David felt he had certain advantages over the younger students in that he had years of experience working and had gained skills that stood to him.

“Coming from a work environment …… every day of the week I was doing presentations on one thing or another and putting PowerPoint presentations together. So I mean that aspect of it was easy for me.”

Ben was of the opinion that “colleges are set up mostly with younger people in mind” and that things like “down time stuff” that the students union were putting on were “completely irrelevant to me”.

Having said that, Ben also stated that he

“got on really well with all the younger students in my class or in my year but ended up kinda hanging out with people in or around my own age.”

Kevin felt that the main difference between the two cohorts was the fact that he was working full-time to finance himself and his studies, which he felt was a stress the younger cohort did not have.

“I was coming in and doing my days in college …… and go straight to work and try and catch back up.”

Liam felt his age and family obligations went against him with regards to energy levels.

“I’m gauging myself against guys in their 20s in class who are able to go to concerts. Getting in early for lectures and things like that I suppose, and having the sheer, I suppose I wouldn’t have the energy.”

However, Liam felt he had “the old maturity to discipline myself” and not get caught up in video games and get a good night’s sleep in order to have the energy for the course.

Mary felt the biggest difference between the two cohorts was that she was now studying purely for enjoyment and without the stress of having to find a job at the end of it.

“I’m doing it for enjoyment now and I’m leaving my options open and completely open minded as to what comes out of it.”

Unlike the younger cohort who she feels

“have to get the qualification and they have to get the job after that.”

Kate, while acknowledging that the younger students do work hard, felt that they have more time and don’t take studying as seriously as the older students. She felt that assignments and exams were “a big deal” for the older students whereas the younger students have skills that the older students do not.

4.3.2 Level of education and experience of formal school

Of those surveyed the average school-leaving age for males was 16.2 years and for females 16.5 years. The average age of participants was males 50 years and females 43.3 years. Just over half of survey respondents did not attain Leaving Certificate standard.

Of those interviewed Liam and Mary reported their formal school experience as positive, while Kate, Kevin and Ben reported it as negative. David reported his experience as both positive and negative, while John reported it neither positive nor negative.

“I just didn’t like school; I wasn’t happy in school. I was a creative child and of course there wasn’t that many creative things going on around me in school so no I didn’t and I left.” (Kate)

Kevin left school at fifteen because his mother could not afford the uniform.

“He [the Principal] gave me a load of verbal so I said that’s it I’m leaving, so I left.”

Ben reported a good experience of primary school but secondary school was a different matter. He changed school a couple of times but still completed his Leaving Certificate. He considers the possibility that

“We weren’t a good fit for each other I suppose; I think that was it.”

4.3.3 Reasons for returning to education

A variety of reasons for returning to education were expressed by those surveyed. Twelve survey participants (or 52%) cited education as their reason for returning to education.

“Needed to up-date my skills and education.” (23)

“To further my education.” (16)

While six survey participants (or 26%) cited employment as their reason.

“I made a conscious decision to change career to increase my employment chances.” (1)

“Wanted a different career path.” (20)

For some participants the possibility of gaining employment in their chosen subject was an unexpected outcome.

“I now intend to pursue a career that I hadn’t seen myself pursuing.” (Ben)

“It’s my life; it’s after putting me in this direction.” (Kevin)

Other reasons for returning were

“To help my children.” (18)

“Cause I was getting nowhere in life.” (15)

“Interest and pleasure.” (8)

Survey participants were also asked why they chose their particular course. A summary is presented in Figure 2.

The majority of participants were in FE to progress their education, followed closely by interest in the subject chosen. Most participants who cited progression as their reason to return were on a Return to Education course, while most of those citing interest as their reason were on a Performance course.

Kate was keen to re-educate herself while at the same time be a role model to her daughters.